News Staff

News Staff![]() -

December 18, 2025 -

Arts & Culture

Whithouse President Gallery

-

627 views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews

-

December 18, 2025 -

Arts & Culture

Whithouse President Gallery

-

627 views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews

Insults in the People’s House: How a President Can Rewrite the White House Gallery—and Why It’s Legal

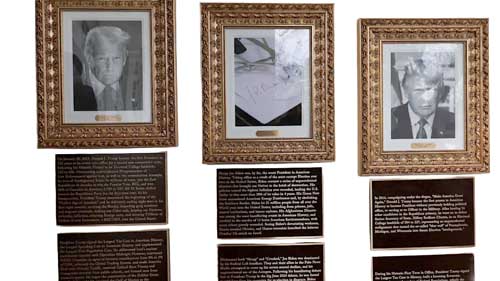

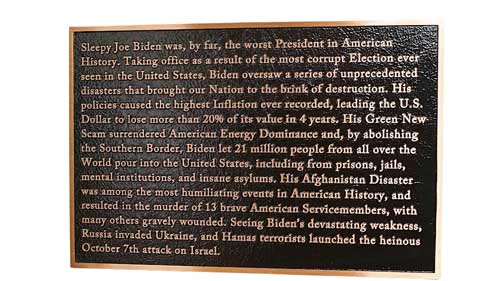

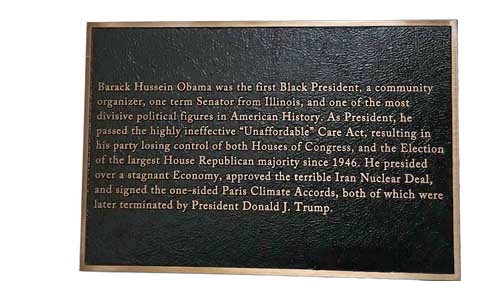

The idea that a single president can hang openly insulting descriptions of predecessors inside the White House feels, to many Americans, like a breach of something sacred. The presidential gallery has long functioned as a quiet civic space—less campaign rally, more institutional memory. Yet President Trump’s decision to co-author new plaques beneath presidential portraits, including harsh and personal attacks on Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, and even fellow Republicans, raises a deeper question than taste or tradition: how is this possible, and is it legal?

The short answer is that it is legal—largely because the White House is not a museum governed by an independent historical authority. It is the president’s official residence and workplace, administered by the Executive Branch. The décor, displays, and interpretive materials inside the White House fall under executive control. Unlike the Smithsonian, the National Archives, or congressionally chartered memorials, there is no statute requiring neutrality, historical consensus, or bipartisan review for internal White House exhibitions. If a president wants to change art, rotate portraits, or alter descriptive text, there is no legal barrier preventing it.

That authority extends to the presidential gallery itself. While custom and precedent have encouraged respectful, restrained language, custom is not law. The plaques described—written in the unmistakable style of President Trump’s political messaging—are not official historical determinations. They are expressions of the sitting president’s views, displayed in a space he controls. From a constitutional standpoint, this is an exercise of executive discretion, not censorship, defamation, or abuse of office in the legal sense.

Free speech considerations also cut in the president’s favor. The plaques represent government speech, not a public forum. Courts have consistently held that when the government speaks for itself, it may advance its own viewpoint. There is no requirement that government speech be balanced or polite—only that it not violate other laws, such as those governing discrimination or incitement, which these plaques do not.

That does not mean the act is without consequence. The real tension here is institutional, not legal. By replacing a portrait of Joe Biden with an image of a signature machine and declaring him “by far the worst president in American history,” the gallery shifts from record to polemic. The inclusion of claims about a “corrupt election,” foreign invasions attributed to “destructive weakness,” and campaign-style self-praise marks a break from the gallery’s traditional role as a unifying civic chronicle.

Presidents have always shaped how they are remembered and how they remember others. What is different here is the tone and the venue. Campaign rhetoric has moved inside the symbolic heart of the presidency itself. The White House, which belongs to no one administration but to the republic, becomes an extension of partisan combat.

Legally, the president can do this because the Constitution gives the office immense control over the executive domain, and because norms are not enforceable rules. Politically and culturally, however, the move invites a broader debate about stewardship. Each president is a temporary custodian of institutions meant to outlast any one ideology. What one administration installs, the next can remove—but the erosion of shared civic space is harder to repair.

In the end, the plaques reveal less about the presidents they describe than about the moment America is living through: a time when the boundaries between governance, grievance, and performance have blurred, and when even the walls of the White House are no longer neutral ground.